Well, a wee bit more than a wee bit more!

Having finally received a copy of the indictment of Ronald (also known as Ranald) and James Drummonds (alias) MacGregor and Callum MacInlester (alias MacGregor) regarding the murder of John MacLaren in 1736, I’m excited to share some rather intriguing information that appears in the document.

As a brief reminder, John MacLaren was in his field plowing when Rob Roy’s youngest son, Robert, approached him and shot him from the rear. The reason given for this act was that John was trying to take over a land lease that was held by, and rightfully belonged to, Ronald. Turns out there was a bit more to this than meets the eye.

The Crown opens by stating that the murder was unprovoked “That the Libel [witness] does not charge the Murder to have been the Effect of any particular or personal Provocation of Injury done by the Person murdered, to the Murderer himself, which might incite him to so bloody a Revenge;”. [1]

A bit of history: The land had been owned, ancestrally, by the MacLarens. When John MacLaren was young, his uncle, Rob Roy (his mother’s brother) was charged with the management of MacLaren’s affairs. So the two were pretty closely related!

According to the transcript, it was stated that by rights, John should have been given the Tack [land] when he came of age but the elder MacGregor chose to renew the Tack to his son Ronald rather than to John. As you might imagine, this would have caused a great deal of disappointment for MacLaren and very likely animosity toward his rival cousin.

Interestingly, in their defence, their attorney argued that this land dispute could not be a valid reason for the murder and therefore the threats made by the defendants, and heard by multiple witnesses, was nothing more than a case of blowing off steam therefore insufficient to prove motive. He stated that the disputed track of land was actually in the possession of Ronald, and the lease still had 14 years to run. So there would have been no challenge to possession of the land by John MacLaren.

However, it came out in court that, it was, in fact, a motive as Ronald had not been reliably paying his rent and so his mother was at the point of breaking the Tack and leasing the land to someone else. [2] And so we have a case where Ronald’s mother, unhappy with his lack of regular payment, considered breaking her lease with Ronald. John, for his part was apparently encouraging his aunt to do so and to then lease the land to him as was his birth right. So this certainly looks to be a possible basis of the animosity between the two families and the motivation behind the murder.

As the proceedings began, the prosecutor made his case that John’s murder was, in fact, a well-planned conspiracy and accused the MacGregor men of conspiring to instigate the murder employing their younger brother, Robert Òg (MacGregor) to do the actual deed, leaving the country as was planned, shortly after the murder.

He offered witness statements pointing to the threats made against John MacLaren.

The first incidence of threat was: “That at a place in that Neighbourhod, called Drumlich, in the Month of December last, the said Ronald declared an Intention to kill the said John Maclaren and told that his Brother Robert was the Person who was to shoot him.”

The second time the desire to murder was mentioned a witness recounts: “That at an other place in the said Neighbourhood, called Innerlochlarigbeg, in the said Month, the said Ronald repeated the same Threatnings.”

And a final witness states: “That in the Month of January thereafter the said Ronald and the other Pannels, renewed the same Threatnings again at Drumlich; the said Ronald adding that though he (meaning his younger Brother Robert Macgregor) shot him (meaning the deceased John Maclaren) through the Head, he the said Robert had nothing to lose.” You’ll note that the narrative uses the word ‘shot’ as if it had already happened which it had not. So I think that was simply the way things were phrased at that time.

Further, “The indictment insists, that the said villainous and detestable Project [plan], formed by the Pannels [defendants] to put in execution by the said Robert, was avowed by the Pannel Ronald, who declared, that if the deceased John Maclaren persisted in taking a Tack of the Lands of Kirtoun, poffeft [possessed] by the said Ronald or his Sub-tenants, his said Brother Robert was determined to shoot him, so soon as he got, from Down, a Gun left him by the deceased Rob Roy his Father.”

All of that was from Ronald and James. But Callum Macinlister had plenty to say as well; if John MacLaren “procured a Tack of land in Kirtoun, he would stick him with a Durk, “or Words to that Purpose”.

So they’ve set the stage and certainly spent time letting everyone know what they had in mind. A “Project”, as the Crown termed it, which was carried out on the 4th of March when Callum Macinlister and a teenaged Robert Òg made their way to the “Fields of Innerlochlarigbeg” with Callum carrying the gun and ammunition that Robert would ultimately use to shoot MacLaren. They joined up with Ronald who was out ploughing in a field not a half mile from MacLaren’s location, and the three huddled together for quite some time. Finally, Callum loaded the gun and set it down on the ground next to Robert. Robert wasted no time in picking it up and, approaching from behind shot John MacLaren in cold blood.[3]

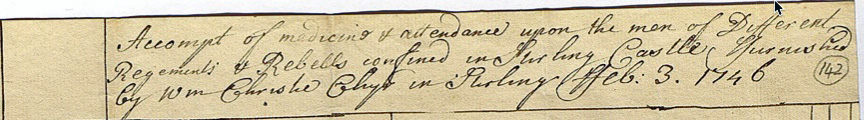

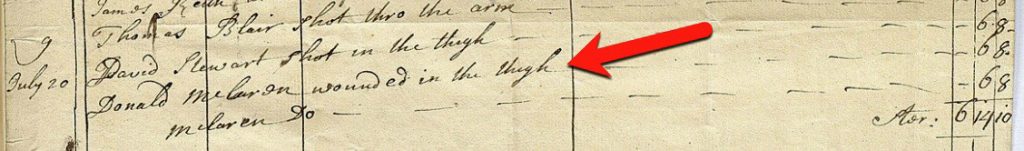

One could suggest that he was a pretty poor shot as they clearly stated in their plans that the idea was to have Robert shoot John in the head. Further, other reports I’ve read mentioned that John had been shot in the back and left to die in the field and/or at some point being carried to his home to die later. So there have been mixed reports. However, I’m inclined to believe the version presented in the court documents which state that he was actually shot in the thigh and left, bleeding, in the field.

Not so luckily for John, the other conspirator, Callum, was waiting nearby and rushed in allegedly to aid MacLaren, stating he had medical skills. But Callum claimed he was unable to treat the wound without knowing what kind of gun and ammunition had been used. Needless to say, the prosecutor wasted no time in catching this lie pointing out that this was the man who admitted carrying the weapon and the shot and powder. He alone had loaded the gun prior to setting it on the ground at Robert’s feet. So it’s pretty hard to believe that he had no knowledge of the weaponry used to cause the injury.[4]

At the time of the murder Robert remained away from the action in his own field and was later reported by witnesses to have boasted “That they had drawn the first Blood of the Maclarens”.

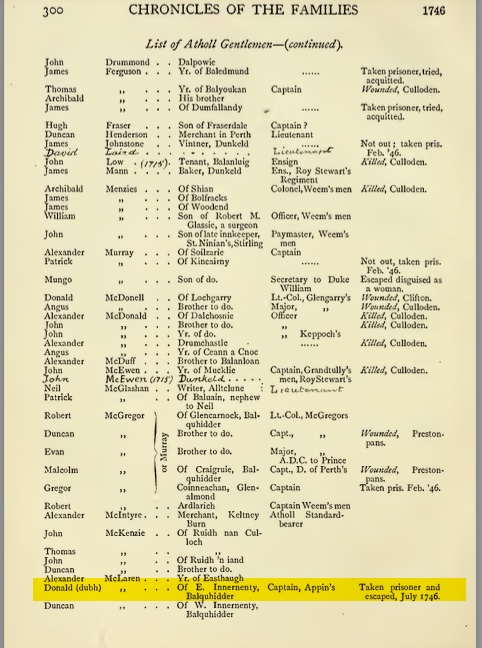

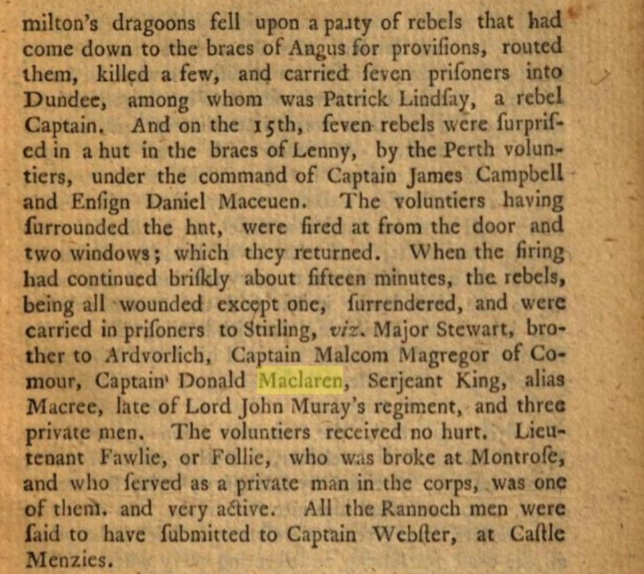

And he wasn’t alone in making prideful statements. Ronald, James and Callum spent plenty of time after the fact publicly singing Robert’s praises for the act of he had committed. At one point saying “that they would have been glad the said Robert had also shot the said Donald Maclaren [sic], the Deceased Friend: And that in case the Maclarens should attempt a Prosecution of the said Murder, it should fare worse with them, and they should very soon feel it to their cost.”[5]

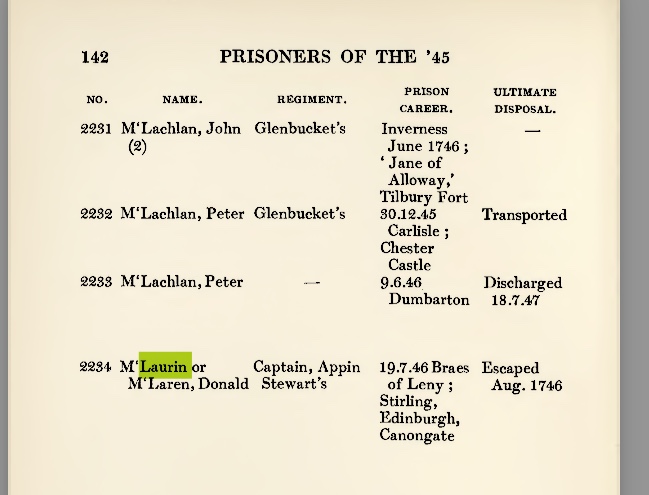

So here we have a possible motive for the attack on Donald MacLaren’s livestock a couple of days later. It’s entirely possible that he learned of the perpetrators and notified the local authorities. This loses impact somewhat when you consider that they spent time bragging in front of witnesses of what had been done. So any one of those people could have reported the crime. Further, because of the nature of the crime I doubt any one person would be required to “attempt a Prosecution” as the local authorities would certainly have done that themselves. That being said, unless it was pure meanness, there doesn’t appear any other likely explanation for the horrible actions they took against Donald’s cattle; an attack that would have had serious financial ramifications for MacLaren.

It isn’t hard to visualise this as a well-planned action. The three men conspiring together months beforehand to commit the murder, huddling with each other in whispered conversation as they laid out their plans. Assigning the actual task to the younger brother who, not yet old enough to have children or land, had the freedom to leave and thus avoid prosecution for the murder. As the other three cooked up alibis so none could be accused of pulling the trigger, they would not be prosecuted and hanged for the murder. Finally, on the fateful day, gathering together one last time in a field near John MacLaren, rehashing the plan and then following through.

The defence capitalised on these alibis, maintaining that there was not enough evidence to include the defendants in the indictment let alone hold them accountable for any part in the murder or the acts levied upon Donald MacLaren’s livestock. He said:

Regarding James: In spite of witness statements, there was no evidence that he had even spoken threatening words. There was no evidence that he had any involvement in the murder. In fact, the defence alleged that James was several miles away at the time of the murder and had been away for several days prior to the 4th of March.

The prosecution’s response was:

- Although James was out of the area at the time, he heartily approved of the murder stating so a few days after it occurred.

- He continued to threaten Donald MacLaren.

- James, along with his brothers and Callum, had a bad reputation.

The Crown argued that if it were a normal, innocent individual he could get away with claiming to be miles from the scene and thus not a part of it. However, James’ reputation and acts of thievery were just as bad as his brothers.[6] In the indictment, there were other crimes charged and one was against James for the theft of a cow from John Maccallum in Vich in November of 1731.[7] Further, having been imprisoned for said theft, took it upon himself to break out prison.[8] This is especially interesting in that he escaped the capital charges against him in the Keys abduction case years later.

Regarding Ronald his attorney stated: His threatening words were just that; words. Empty threats made as a release of emotional anger. And since there was no charge of murder against him, his words were irrelevant and insufficient evidence to hold him accountable. Further it could not be reasoned that he went to the fields that day specifically to meet with his fellow conspirators.

The fact that he was out plowing at the time of their arrival proved that he was there for the purpose of farming. And since the murderer was his brother it would not be considered unnatural or unusual for him to stop his plowing and go to speak with him. The way the defence phrased it was “his being in the Fields behoved to be imputed to Accident, and not to Design”. He supported this by saying that Ronald was actually helping out his mother by plowing her field – an excuse he would use later on as well; helping his mother.

The prosecutor responded to each of the defence points with:

- The threats he made go well beyond a simple spouting off. The fact the he repeated them some four times lends weight to his seriousness in carrying them out and they were heard by a large number of people (45 witnesses are listed in the indictment papers).

- Since the field he was plowing was only a half mile from where John was killed and his threats and reputation pointed to a man unworried about committing crimes, his innocent ‘helping his mother’ defence could easily be seen as a guise to cover up his participation in the murder.

- Further, his bragging after the fact and his threats of violence against Donald MacLaren did not lend weight to his comment that he was simply helping out his mother.

Ronald was also accused in the indictment of theft; stealing a horse from Duncan Miller in Aberfoil and, in 1733, stealing two horses from Euphame Fergusson in Cullichbray.[9] Again, these additional charges helped the Crown to solidify Ronald’s reputation as nefarious and no good.

Let’s take a look at what the defence had to say about Callum: He was not to be held accountable for making threats prior to the murder because no one could pinpoint a location where he was heard making them therefore they meant nothing. And even if he did make them, how could they be taken seriously when he rushed to give medical aid to the dying man? And here is where it really gets a bit far fetched….

He claims that being in a field with a younger man and a loaded gun that he placed upon the ground could happen to “the most innocent Man”. He said that he they had been sport shooting, killing several small birds as he taught Robert how to shoot and it would be “a danger Example to all Mankind to infer any Suspicion of Guilt from what is done every Day by the most innocent Persons”.

Yeah right.

But what about leaving MacLaren to bleed to death? Well, according to Callum, it was “necessary” to know with what the gun was loaded. And even if he knew he had no instruments with him, so he was unable to do anything to help MacLaren. He claims to have sent for his instruments “with all possible speed” and that as soon as they arrived he gave aid to the victim to the best of his ability.

As you might imagine this did not go down well with the prosecution. The prosecutor stated that Callum’s previous threats offset any claim of innocence. And his excuse that he and Robert Òg were simply shooting birds doesn’t hold water either as what he was actually doing was teaching Robert how to use the gun. And to expect the court to believe that he simply and innocently laid the gun on the ground whereupon it was immediately picked up and carried off to commit the murder was a little over the top.

Further, how could Callum not know the powder that was used when he himself had loaded the gun. He addressed the excuse that Callum had no instruments by stating: “As to the pretence of wanting Instruments to dress the Wound; that needed not have delayed Endeavours to stop the Blooding, which possibly might have saved the Defunct’s Life.; and though the Instruments had been at hand, it would have been absurd and wicked to have used them, until the Blooding was stopt, which was to be done only by Bandages”.[10] He went on to characterise the failure to address the wound “…it was absurd Pretence for delaying to stop the blooding of the Wound” and in essence accused the defendant Macinlester of using the lack of knowledge of the ammunition and thus fail to render aid as an excuse designed to absolve him of any participation in the crime. These were not baseless suppositions on the part of a prosecutor who clearly saw through the thin veil of guise. Because they also had proof that directly after the murder and before attending to the wounded man, Robert rejoined Ronald and Callum for a post-act “consultation”. So clearly, Macinlester knew all there was to know about it![11]

You have to hand it to them. It really was pretty well planned and they seemed to have tried to foresee how each of their actions would be perceived and provided alibis to cover themselves.

But the prosecution was not done. And he had plenty to say. Basically he argued that the reputation and previous criminal records of the defendants must be taken into consideration. He noted that, unlike honest men, those engaging in criminal acts were well versed in “covering the Evidence of Crimes which is acquired by Habit and long Practice in Villanies.” Good point.

That was a general statement but he continued, aligning it with the defendants’ actions. “The Pannels, all and each of them, are habite and repute, and bruited in the Country, to be common and notorious Thieves and Stealers of Horses and Cows and Refsetters [resellers] of Theives and stolen Goods, knowing them to be stolen.” He states that “circumstances’ taken one at a time are inconclusive. But when they are taken all together they “often give a legal Certainty in Criminal Trials”.

He then responded to the defense’s arguments point by point:

First, that each of the defendants are habitual common and notorious thieves with reputations.

Secondly, “the Age and Circumstances of the Person who is this Case committed the base and cowardly, as well as cruel and bloody Murder” was influenced and used by the defendants.[12]

Thirdly: The threats they made having been followed by the murder was sufficient “Proof of Guilt” to hold them accountable.

Fourth: There was sufficient time between the threats having been made and the act itself for the men to conspire and form a plan to take the “Life of an innocent Man”.

Finally, in support of his argument as to their reputations playing an important part in judging whether they were complicit in the crime, he included past offenses for which Ronald and James were charged. One of which was pretty horrific…

The severe beating to the point where he was in “Danger of his Life” of a John Stewart of Lickinscridane when he asked for restitution of a cow that the MacGregors had stolen from him. The defence claimed the cow was purchased by John from a tenant of the MacGregors who had failed to pay his rent. Therefore the cow could be taken by the MacGregors to cover that payment – in spite of the fact that the tenant no longer owned the cow. Apparently this was something the law allowed but only if the animal was located on the land rented by the tenant (which it was not). But even if it had been, the prosecution argued, that did not give the MacGregors the right to beat the man nearly to death.[13] I think it’s needless to say that the Crown made its point about the vicious behaviour of the MacGregor boys and their accomplices.

However, the charges didn’t stop with the murder of John MacLaren. They also included the horrific acts against the cattle owned by Donald MacLaren. The charges read: “That upon the 9th Day of March last, they and their Accomplices, under Cloud of Night, came to the Lands of Innernenty-Easter, possessed by the above-mentioned Donald Maclaren; and in a wicked and malicious Manner, killed, houghed [hamstrung] and destroyed near forty Head of young Cattle belonging to the said Donald”. [14] The Crown went on to propose that these acts were a result of the threats that the MacGregors made against Donald MacLaren prior to John’s murder.

Note: The law read that, basically, harm/death caused to cattle during the season of giving birth was a capital offense. This offense was apparently committed during a season of giving birth so the consquences were pretty dire should they be convicted.

The defence, in an effort to mitigate the charges and keep his clients from the noose, argued that although this was at the time of year of calving, the animals were too young to be giving birth so these charges should be dropped.

Further, the defendants admitted that yes, they were in the vicinity, but were simply visiting Ronald’s mother where they stayed the night.

On the way to her house their road passed by Innernenty [sic]. But, Kirktoun and Innerlochlarigbeg are both on the north side of two lochs and a small river and the road from one to the other is a direct line along the north side of the lochs and river – roughly four miles. However, Invernenty is located on the south side of the lochs and river, barely a mile from Innerlochlarigbeg. Due to the location of these places and the evidence of their whereabouts hours before the houghing, it was apparent to the prosecution that the defendants went well out of their way if a visit to Ronald’s mother was, in fact, their intended destination and not a place they visited after committing the crime.[15]

Not surprisingly, the Crown took issue with the defendants’ argument. He pointed out that the law actually reads horses, oxen and “other Cattle, which extends it to Cattle of all kinds”.[16] And the law relates to the barbarity of the deed, not the season in which it was committed. This was a serious matter as the punishment for houghing and killing cattle was death.[17] Clearly they had a lot to lose if convicted on those grounds.

Ultimately, Ronald, James and Callum were held in prison and bound over for jury trial in June of 1736. Robert as nowhere to be found and would never face prosecution for his part in the murder.

The verdict is not available in these papers but we know from other sources that these men were all acquitted with probation and a fine.

So I think you could safely argue that they got away with murder.

Source

Information for His Majesty’s Advocate, for his Highness’s Interest Against James and Ronald Drummonds alias Macgregors, Sons to the deceased Rob Roy alias Campbell Macgregor, and Callum Macinlester alias Macgregor, Pannels. July 21, 1736

[1] Information, page 2

[2] Information, page 17

[3] Information, pg 4

[4] Information pg 5

[5] INformaton pg 5

[6] Information pg 12-13

[7] Information, pg 19

[8] Information, pg 20

[9] Information, pg 20-21

[10] Information pg 16

[11] Information, pg 15

[12] Information pg 10-11

[13] Information, pg 21-22

[14] Information pg 17

[15] Information, pg 19

[16] Information, pg 18

[17] Information, pg 19