A lot has been written about Rob Roy McGregor and much of it whitewashes his and his clan’s behaviour. But Clan Gregor’s ongoing dispute with the MacLarens didn’t end with the 1558 massacre. Two centuries later the MacGregors were still finding ways to inflict misery on the MacLarens.

As one story goes, Rob had three sons, James, the eldest, Ronald (or Ranald), the middle son and Robert, also called Robin Òg (Young Robin) as his youngest. It has not been confirmed that the immediate family also included a cousin by the name of Duncan (we’ll meet him a bit later).

Back in the 1730s Ronald had found a willing woman and was preparing to marry and looking for a farm of his own. In 1734 John MacLaren, holding the title Baron Stoibchon and Chief of Clan MacLaren was leaseholder of some very desirable farmland in Wester Invernenty. This looked like the perfect place and Rob set about securing the land for his son. Conveniently, that year the lease was due to expire which would mean others could petition to take it over.1MacLaren, Margaret, The MacLarens, A History of Clan Labhran, 1960, pg. 67

I say ‘one story’ because there are several conflicting versions of who was actually leasing that land. For example: in the preface of a book entitled The Trials of James, Duncan, and Robert McGregor, Three Sons of the Celebrated Rob Roy before the High Court of Justiciary, in the Years 1752, 1753 and 1754, the authors provide a different scenario. They write that “McLaren, a kinsman of the McGregors, though of a different tribe, had given the offense by his proposal to take a lease of some land in the possession the McGregor family”. 2The Trials of James, Duncan, and Robert McGregor, Three Sons of the Celebrated Rob Roy, before the High Court of Justiciary, in the Years 1752,1753 and 1754. (Edinburgh: 1818), pg. civ

According to two life of Rob Roy books that I read, the land had been held by Rob’s cousin Malcolm who had died suddenly leaving children too young to inherit the lease and work the farm. Because of this the land reverted to its owner, the Duke of Atholl. The Duke in turn chose to sell the land to Lord Appin. Appin, in turn, granted the land to John MacLaren.

This sounds good and would certainly explain the animosity between the two clans. Yet there is a discrepancy here as well as we’ll see later in this article when we examine a letter to Atholl’s estate manager. In that letter, the writer asked the estate manager to let Atholl know about the situation and to take actions against the MacGregors. If Appin were, indeed the land owner, it would make no sense to petition Atholl to take action against the MacGregors as the letter requests. That responsibility would have been held by the person overseeing the land. It would be highly doubtful that Atholl would be overseeing Appin land holdings.

Further, according to the information provided in The Trials book, in the legal indictment for the trial of James and Ronald for the killing, the motive for the murder was to prevent John from “competing with him (Ronald) for the lease”. The prosecution went on to say that before the murder was committed, John MacLaren was threatened multiple times by the MacGregors stating that Robin would shoot him as soon as he was able to get his father’s gun which was being repaired. John also received threats of death by dirk, if he tried to get the lease in spite of the death threats. 3The Trials, pg. cv At one point, Robert argued that the land belonged to his mother – more on that later.

After John MacLaren’s killing, the indictment reads that Robert returned to his mother’s house and bragged of his success. Meanwhile his brother James and a relative called Callum McInlister, who apparently was part and partial to the crime, praised Robert for the crime and expressed their ‘wish’ that Donald MacLaren had met the same fate.

Since they had James and Callum as accessories to murder, the authorities also levied charges of various crimes of theft and fencing stolen goods. The court referred to them as “notorious thieves and resetters of stolen goods”. This included cattle rustling. So these guys weren’t the innocent victims of persecution as some MacGregor chroniclers have painted them.4The Trials, pg. cvii

Further, it doesn’t appear that there was ever any doubt that Robert was the murderer as multiple witnesses attested at the trial of James and Callum. As one witness, a Robert Murray of Glencarnoch testified when visiting the house of Rob Roy’s widow the same night that MacLaren died: “he saw Rob Oig there with a gun: That he asked him why he had shot McLaren? To which Rob answered, that the deceased had attempted to get his mother’s possession; and that if the McLarens persevered in giving offence, their misfortunes were only beginning.”

All of this plus the defence’s argument that MacLaren never took possession of the land in question brings the timelines given in MacLaren’s, Murray and Trantor’s books into question because all of them state that MacLaren acquired the lease at some point prior to the killing. 5The Trials, pg cix Yet here we have Robert claiming that the land belonged to his mother, a letter to the estate steward suggesting the land belonged to the Duke of Atholl, and three books relating that the land was under lease to John MacLaren. So who did own this land?

Well, it was a leasehold so if Robert’s mother owned it, she would have been the lessor and there is no mention of that anywhere in any document. From the documents I’ve read, I believe the owner was the Duke of Atholl. Appin played no part in this event. Still, that doesn’t explain the discrepancies as to when or if John MacLaren ever took possession of the land for which he was allegedly killed.

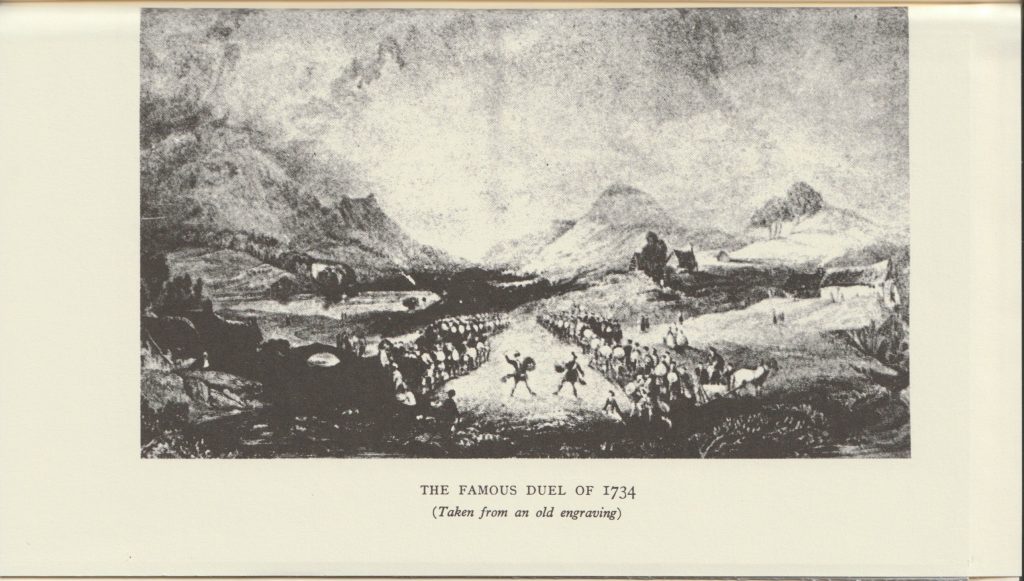

Going back to the books on Rob Roy’s life and Margaret MacLaren’s book on the MacLaren history, we are told that at some point, having been forewarned that there would be trouble,6The Trials, pg. cxi , MacLaren called for assistance from the Stewarts ‘over the hill’, and Appin responded with 200 men. The two groups of men met below the Kirkton of Balquhidder.

Rob Roy did not bargain for this, however, and realising that he and his men were terribly outnumbered determined that the cost in blood of battle would not be worth any gain he might achieve if he were successful. But that didn’t mean he’d given up – far from it. He requested a meeting with Appin wherein they agreed to settle the matter through a duel. Should Appin’s man win, MacGregor pledged that Clan Gregor would relinquish any claim to the Invernenty land. This might lead us to think all was well. But remember, we’re dealing with Clan Gregor here and their reputation pretty much guarantees that would not be the case. And sure enough it wasn’t.

Again, there are a couple of versions of the duel, but both Rob Roy books that I read relate the duel in pretty much the same way. In one book the author tells us that Rob Roy took the role of combatant himself so that “no one might think he had shirked a fight he offered himself for a trial at arms”. 7Murray, W.H., Rob Roy MacGregor, His Life and Times (1982) This, to me, does not sound right based on Rob’s history of avoiding fights/battles and weaselling his way out of trouble. Margaret MacLaren deviates from those renditions writing that Rob Roy was one of the finest swordsmen in the country and bragged that he’d never lost a fight. He declared that this one would be no different. 8The MacLarens, pg. 68 This seems more reasonable to me and more what I would expect from Rob Roy MacGregor. Further, he risked nothing, as was typical for Rob, as this duel would be a duel of honour which meant it would end at the drawing of first blood not at the death of one of the combatants.

Alasdair of Invernahyle, a brother-in-law to Appin was chosen as the Appin champion. He was a robust young man reputed to be an excellent swordsman. The weapons agreed upon were broadswords and shields.

The two fought in what was probably a fairly brief but well-matched battle until Alasdair inflicted a wound to Rob, thereby drawing first blood and ending the duel. The MacGregors kept their word, relinquishing any claim to the Invernenty land and John MacLaren was left to farm in peace. Well, almost.

It’s probably needless to say that after a bitter loss, an injury that eventually killed him and the loss of face, Rob Rob MacGregor was not a happy man and certainly had no love for John MacLaren. In fact, when John visited him shortly before his death for reasons unknown (most sources agree the reason remains a mystery), the tension was palpable, and the meeting was highly formal. Rob, with the help of his wife refused to meet his “enemy” looking weak so managed to get up from his bed and dress for the occasion. It was likely the last time he rose.

Before he died, Rob had one last go at MacLaren whom he saw as the cause of all his miseries. As I said before, it does make you wonder why Rob held such a strong hatred for MacLaren; John MacLaren did not steal the land from him. From what I read in MacLaren’s book, John was on the land long before MacGregor decided he wanted it.

At any rate, according to the two Rob Roy biography sources, McGregor was told by a priest that he could receive absolution only if he truly repented; and this included forgiving John MacLaren, something he was loath to do. Each of the two sources I read offered a different version of Rob’s last moments of life but both mention this absolution requirement.

One source makes no mention of his son, Robin Òg being present, the other places Robin at the foot of his father’s bed. 9Tranter, Nigel, Rob Roy MacGregor (1995), pg. 185And what this book reports is most interesting and would certainly explain the next part of our story. Reportedly the priest present forced the issue of John MacLaren, speaking his name specifically as someone Rob needed to forgive. Grudgingly Rob voiced that forgiveness. But, according to the book Rob ‘raised his eyes to the foot of the bed where his younger son Robin Òg stood watching’. ‘I forgive my enemies, especially John MacLaren’ and after ‘catching Robin’s eye” said ‘But see you to him!”

Whether this is true or not is not documented but one fact does run through the historical documents, the MacGregor boys held John MacLaren responsible for the death of their father and set about to exact revenge upon him.

On March 4th in 1736 Robin Òg, carried through on the threats he’d been making to kill John MacLaren. Accordingly, along with his two older brothers, Ronald and James, and several other men, accosted John whilst he was plowing. Seeing the MacGregors approaching, John said to a companion “What does that snake want?”. We’ll never know what discussion, if any, passed between the men but once his back was turned, Robert, using his father’s Spanish long gun, killed John MacLaren, in cold blood, shooting him in the back leaving John for dead. He did, in fact, die later that night.

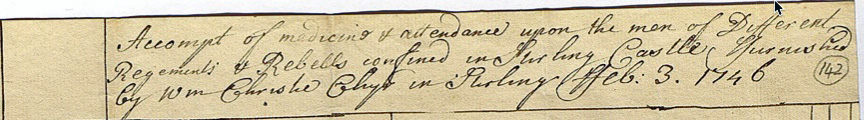

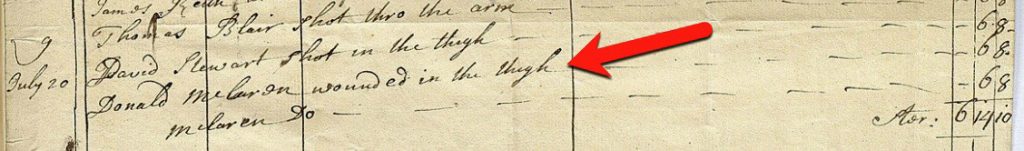

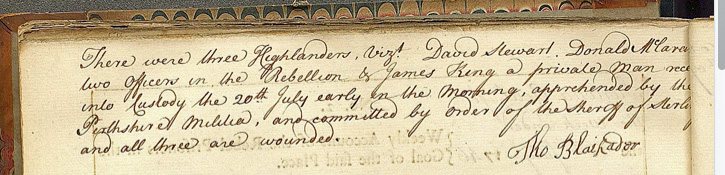

But the MacGregor boys were not done with the MacLarens quite yet. A few nights later, on the 9th, the brothers MacGregor in the company of several other men (probably the same who had accompanied them to the MacLaren shooting) visited the farm of Donald MacLaren (the same Donald the Drover we met in the last couple of articles) and set about killing and/or maiming 30 head of Donald’s cattle. As Donald made his living droving, this would have had substantial financial impacts on his livelihood. And, again, I’ve not found any reason other than hatred for the MacLarens to carry this vengeance down the road to Donald MacLaren who was not, at least in the records or any book I’ve read, noted as a party to the land dispute.

Margaret MacLaren gives us the following letter written by Alastair Stewart of Invernahyle to Alexander Murray who was Atholl’s estate manager in 1736 wherein he describes the horrific events. The letter, found in the Chronicles of the Atholl and Tullibardine Families, ii, 415 is dated 13 March, 1736 and reads:

“Sir, –Upon the 4th Instant their[sic] happened a most barbarouos action in this country in the hands of Rob Roy’s youngest son. He came with a gunn and pistle to the Town of Drumlich where John MacLaren, Baron Stoibchon and Wester Invernenty liv’d, and the said Baron with two of his neighbours being att the pleugh, this youngest son of Rob Roy’s called Robert, came to the pleugh, and without any provocation, as the Baron was holding the plough, shott him behind his back, of which wound he dyed that night.

Tho’ this wretch was the unhappy executioner, yet it is thought he was sett upon by his Brothers and others of their adherents to commit this tragicall action, as will appear by their conduct, for upon the 9th, they not wearying of their vile practices, they hough’d (hamstrung) and kill’d upwards of 30 stotes (bullocks) belonging to Donald McLaren, Drover, in Innernenty, and threaten frequently to shoot himself and some others of his Clann.

I happening to be in this country att the time, and being desired by Stoibchon’s friends to represent these vile practices that you might fall on proper methods to curb such vilious practices, and acquaint his Grace of all that happen’d in this affair, and in the mean time that you send express orders to your Baillie here to make a closs (strict) search for the malefactor, and impower him to raise the whole country for that effect.

It is the generall opinion that this hellish plot hath been concerted by Rob Roy’s three sons and their adherents, and I humbly think they should all be seas’d if possible and banish’d the country. I doubt not his Grace will endeavour to free his country of such vile wretches.

In the mean time I am hopefull you’ll have Regard to the present dangerous situation of several people in this country that have been threatn’d by these wretches, and cannot safely come out of their houses without arms, and are oblidged to watch their houses and catle least they sufferr the same gate with the stotes, which doubtless will happen if the Superior of the country does not immediately quell this affair. Expecting your answer pr. Bearer, I conclude with my compliments to you, and am, Dr. Sir, r. humble sert..

Stewart of Invernahyle.

John Stewart, brother in law to the defunct.

Do: McLaren, att Innernentie

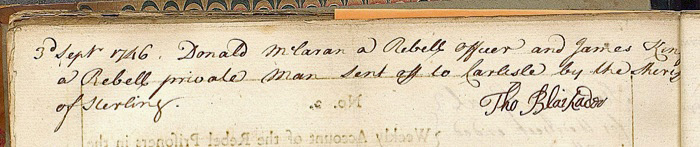

At this point young Robert (Robin) left the area so we pause his story there and come back to him later.

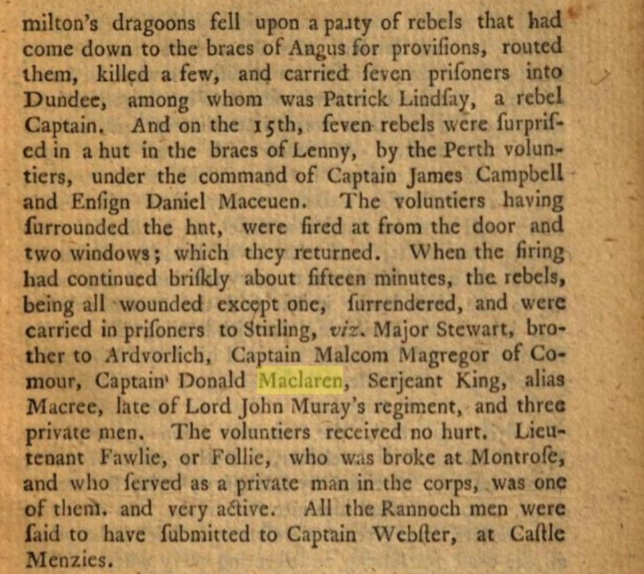

John’s death did not go without notice. In the 15 March issue of the Caledonian Mercury this following article appears:

“That John Maclaren of Beanchon, in Balquhidder, Perthshire vassal to His Grace the Duke of Atholl, was the 4thinstant barbariously murderd by Robert Drummond (alias Macgregor), commonly called Robin Oig, son of the deceased Rob Roy Macgregor, by a shot from a gun as he was ploughing without the least provocation, whereof he instantly died; thereafter he and others, his accomplices, went to the town of Invernenty, and houghed, mangled and destroyed 26 stots and a cow belonging to Malcolm and Donald Maclaren, drovers. Therefore whoever shall apprehend the said Robert, so as he may be brought to trial, shall have 20 guineas reward from James Muirhead, at his coffee-house. He is a tall lad, aged about 20, thin, pale-coloured, squint-eyed, brown hair, pock-pitted, ill-legged, in-kneed, and broadfooted.” A second notice on April 22d noted that Robert Stewart of Appin was prepared to pay £50 sterling for the capture of Robin Oig “of the tribe of Clan-douilcheir”

So here we have an interesting conflict in stories between those written by chroniclers of Rob Roy’s life, court documents from the trial of James and Callum, newspaper articles and documents of the time. It appears that, according to the Caledonian MacLaren was the vassal of Atholl, meaning the land actually belonged to the Duke of Atholl and that confirms that Appin was not involved in its ownership at all! This also confirms that he did have rights to farm the land prior to his death. But it also downgrades the number of cattle affected in the second attack on Donald MacLaren and names another MacLaren, Malcolm, as an additional victim of the cattle raid. Personally, I would tend to rely upon the witness, John Stewart, the author of the letter to Atholl’s estate manager.

At any rate, Robin/Robert having fled the area was nowhere to be found. But his brothers remained and Ronald, James plus one of their accomplices, Callum MacInleister, were charged as accessories to the murder. All three were released eventually but the court found Ronald and James to be “bad characters, and beasts not rightly come by, and that might be speered [asked] after”. In other words he wanted them watched. They were ordered to pay £200 and watched for seven years to ensure their good behaviour. This, to me, sounds like what we would call probation nowadays.

Although that’s the end of our story relating to the MacLarens, following Robert and his brothers’ exploits is interesting in and of itself, and it does bring closure to the death of John MacLaren albeit many years later.

At one point in the mid-1700s Robert MacGregor, alias Campbell, alias Drummond, alias Rob Roy, now going by the name of Robert Campbell, returned to Scotland from France where he had exiled. Back at home and back to old habits it seemed as on December 8, 1750 the boys, now men of course, kidnapped one Jean Key of Edinbelly.

Jean Key was a young widow, age 19 and an heiress that was left pretty well off by her late husband. Reports say that Robert, without any means of his own, conspired with his brother James to marry a rich widow. So they set about accomplishing this when they learned of the passing of Jean’s husband two months prior. This was not something she agreed to – in fact she’d never even seen him. But she had been warned by her neighbours that they had heard rumours of people in town who had designs on her money. So when Robert sent a note soon after the death of her husband saying he would like to meet with her regarding a proposal of marriage she, understandably, declined. According to the records, this infuriated Robert who was reputed to have a horrific tempter. He once again got together with his brothers Ronald, Duncan and James to plan a kidnapping and forced marriage with the young widow.

Accordingly, on December 8, 1750 they did just that. Ronald took the lead on this one and Jean was brutally abducted, forced into marriage and then raped by Robert under the guise of being her husband.

The three brothers were eventually caught and brought up on charges of “Hamesucken” (taking someone forcefully from their own home), forcible abduction and carrying away of Jean Key, holding her prisoner against her will and in the case of Robert, ravishing (rape).10The Trials, pg. cxxiii

Robert was already considered a fugitive due to his failure to appear at trial for the murder of John MacLaren. When he was finally caught he was brought up on charges of murdering John MacLaren as well as the abduction of Jean Key.11The Trials, pg. cxxiii Not surprisingly law enforcement was not at all unhappy to have him finally in custody.

Although the MacLaren matter was not mentioned as part of the charges read at Robert’s hanging, it’s likely they played a part in his trial and sentencing, and they are mentioned several times in the trial transcript.

So on February 17, 1754 Robin Òg was hung by the neck until dead in Grassmarket. The account in the Caledonian Mercury 17, February 1754 is fairly graphic and very descriptive of what I take to be his last words wherein he blamed his sins on his “swerving two or three years ago from that Communion”. But we know he swerved a lot longer that ‘two or three years ago’ – the death of John MacLaren and destruction of MacLaren livestock was some 20 years before. Albeit not directly for the death of MacLaren, in the end at least his killer was caught and executed.

As for his brothers, James escaped from prison before sentence could be levied and died not long after in France. Ronald, although mentioned in James’ trial doesn’t appear to have been brought up on charges. However, their other brother Duncan was charged with the same crimes as James and Robert but found not guilty by the jury.

- 1MacLaren, Margaret, The MacLarens, A History of Clan Labhran, 1960, pg. 67

- 2The Trials of James, Duncan, and Robert McGregor, Three Sons of the Celebrated Rob Roy, before the High Court of Justiciary, in the Years 1752,1753 and 1754. (Edinburgh: 1818), pg. civ

- 3The Trials, pg. cv

- 4The Trials, pg. cvii

- 5The Trials, pg cix

- 6The Trials, pg. cxi

- 7Murray, W.H., Rob Roy MacGregor, His Life and Times (1982)

- 8The MacLarens, pg. 68

- 9Tranter, Nigel, Rob Roy MacGregor (1995), pg. 185

- 10The Trials, pg. cxxiii

- 11The Trials, pg. cxxiii